The elderly lady with pneumonia was breathing well at morning rounds. But when Ronnie Mathews, M.D., visited her hospital room that afternoon, he noticed her breathing was more distressed. He moved her to the intensive care unit and began treatment to prevent respiratory failure.

|

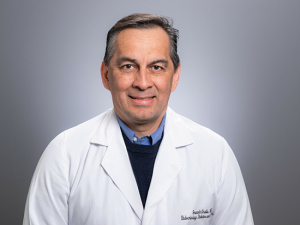

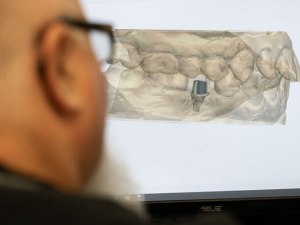

| Ronnie Mathews |

The patient didn’t have to wait for a nurse to call her primary-care physician or for her doctor to arrive. Because Mathews is a hospitalist — a staff doctor who provides inpatient care — he was able to take immediate action.

Less than 10 years ago, hospitalists were a new concept; today the specialists are found in most major hospitals. The UAB Hospitalist Service was the first hospitalist group in Alabama when it opened in 1998; Medical Director James Lyman, M.D., says today the service is staffed by eight hospitalists and five nurse practitioners.

“There are tangible benefits in having a hospitalist available 24/7 to monitor patients and coordinate their care,” Lyman says. “We can assess and respond to emergent changes in their conditions. National studies have shown this reduces lengths of stay and costs and increases patient satisfaction.”

“Hospitals have become complicated places,” Mathews adds. “We understand how to navigate hospital processes and guide the patient. We are familiar with new technologies that might be beneficial, because we use them every day. We also are able to follow up as soon as test results come back, which saves time and money and gets patients home to their families faster.”

The physical presence of a doctor also reassures family members, Mathews says. “We can answer questions, handle acute situations and play a preventive role, helping to improve glucose control and prevent infections and other complications.”

Instant attention

Just as heart patients are referred to a cardiologist, general medicine patients can be assigned to the UAB hospitalist unit by referring physicians. Primarily, UAB hospitalists work with patients admitted for an acute medical illness or a combination of illnesses. “Working with the complexities of caring for patients with acute conditions is a different kind of medicine,” Lyman says.

Hospitalists have a set of skills that primary-care physicians appreciate because they benefit the patient and their practices. “They don’t have the stress of needing to be in two places at once. They don’t have to choose between seeing patients in their office or rushing to the hospital if a patient is having problems,” Mathews says. Because physicians in private practice may have only one or two hospitalized patients on any given day, “it can be a relief for them to have a hospitalist watching over these patients,” Matthew says.

Many physicians still visit their patients, but they can do it when their schedules allow because their patients are being attended. “We stay in touch with each patient’s doctors to keep them in the loop — briefing them on tests, findings, medications and developments — and we work closely with them when the patient leaves the hospital,” Mathews says.

Mathews adds that hospitalists also help enhance processes throughout the medical enterprise because “hospitalists see what is working and what can be improved, so we can be advocates for patient care.”

In particular, hospitalists often make recommendations related to quality management and patient safety and satisfaction. These may include increasing the efficiency of processes in the emergency department so that patients don’t have to wait as long for rooms, identifying computer or equipment problems or developing procedures to prevent medication errors.

“Hospitalists are ideally suited to recognize opportunities for improvement,” Lyman says. “We may care for patients in only one unit, but we can help thousands who come through the hospital.”

Role in geriatric care

Hospitalists likely will have an expanding role in the delivery of health care, particularly for an aging American population that is more frequently hospitalized with complex conditions. Hospitalists have been an integral part of the care team in UAB’s Acute Care for Elders (ACE) Unit since it opened in July 2008 within UAB Highlands hospital.

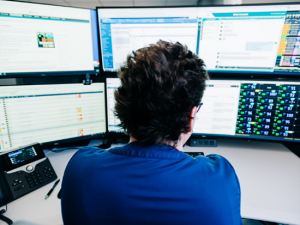

Hospitals stay in close contact with patients’ primary physicians to keep them updated on test results, changes in condition and other news.

The goal of the unit, according to its medical director and geriatrician Kellie Flood, M.D., is to anticipate and prevent new geriatric problems in elderly patients while managing their acute care. “Geriatric patients in a hospital setting may be prone to developing acute confusion, falls, pressure ulcers, incontinence, and other problems less often seen in younger patients,” she says. “They may have multiple geriatric issues in addition to their acute medical problem. They also are at increased risk of functional decline during a hospitalization.”

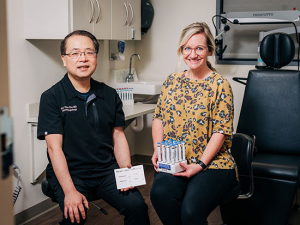

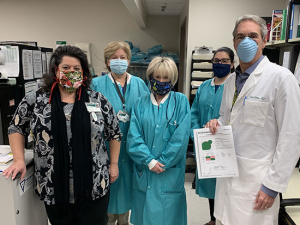

No one person has time to adequately address all of these issues, “so we work as an interdisciplinary team,” Flood explains. The ACE Unit team includes physical therapists, respiratory therapists, occupational therapists, nurses, dietitians, pharmacists, social workers, volunteers and a pet therapist — with hospitalists as attending physicians.

The hospitalist model is a perfect fit for the ACE Unit, says Flood. “Our team meets every day to discuss how patients are doing and what we’re observing from a geriatric standpoint. Are they eating? How’s their muscle strength? Are they depressed or showing signs of cognitive decline? We do medication reviews to make sure they don’t have multiple prescriptions putting them at risk for an adverse drug event, a fall or confusion. We work to promote mobility and cognitive stimulation to help them avoid developing new complications.”

Studies show that the ACE multidisciplinary team model of care helps to improve function, reduces length of stay, increases patient satisfaction and results in better outcomes — findings that are similar to survey responses about hospitalist care. “We use what has proven to work and build on it,” Flood says.

Communication and compassion

Becoming a hospitalist doesn’t require additional medical training — most hospitalists have completed residencies in general or internal medicine — but it does require some key expertise. “You need high-level interpersonal and communication skills to explain what’s happening to the patient and work closely with the referring physician,” Lyman says. “You should be adept at using information technology for systematic communication and the appropriate handoff of records when patients are discharged. A hospitalist also has to be comfortable with multitasking. It’s not uncommon to be reviewing a chart when a pager goes off, sending you to treat an unstable patient. You have to be able to change with the events of the day and go with the flow.”

Patience also is paramount, Mathews says. “If a patient doesn’t have a primary physician or comes to the emergency department and records aren’t available, we have no baseline. We have to begin at the beginning to get a good medical history.”

Lyman echoes that point: “The first time you meet a patient, it’s usually in an acute situation with the patient and family under stress. You have to develop the doctor-patient relationship.”

Despite the challenges of working in a hospital all day, Lyman and Mathews enjoy being hospitalists. Their schedules are more predictable than those of other medical specialists, and both men agree that inpatient medicine is exciting and dynamic. “We see a variety of patients and many interesting cases,” Lyman says. They also are proud of what they have accomplished as hospitalist pioneers in Alabama and are eager to see how their field evolves and influences health care. “There are many rewards, and I enjoy what I do,” Mathews says.

—UAB Magazine