One of five 3D filament printers in the Sterne Library 3D Printing lab on the library's ground floor.

One of five 3D filament printers in the Sterne Library 3D Printing lab on the library's ground floor.

ANDREA MABRY | University RelationsUAB has always thrived on atypical collaborations. Nevertheless, it is not every day that you will find a librarian, a nutrition scientist and a performance director from UAB Athletics meeting to tackle a tough problem, as they did one afternoon last year at the Football Operations Facility.

That librarian was Dorothy Ogdon, head of Emerging Technology and System Development for UAB Libraries, who presides over two of the most heavily trafficked 3D-printing labs on campus. So when she reached out with an offer to connect the Reporter with people doing interesting things using 3D printing across UAB, we jumped at the chance.

Here is a look at how staff, students and faculty are using 3D printing in real research, education, clinical care, athletics projects and air conditioning units across campus.

Scroll down or use the links to jump to each use case — and if you want to know how to start your own 3D-printing project, Ogdon explains it all in "Getting started with 3D printing at UAB Libraries” below.

Keeping the lights on for muscle research

Custom case for UAB Football GPS units

Fixing failed controllers on HVAC units across campus

Novel teaching tools for professional students in the health sciences

Chips for disease modeling and drug toxicity testing

Stretching and pressuring heart cells as they mature

Custom applicators for radiation therapy

Creative looks for up-cycled soap

Printing guides for dental implant surgery

Haley Nesmith Patton, doctoral student in the Department of Biomedical Engineering

Haley Nesmith Patton, doctoral student in the Department of Biomedical EngineeringANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Project: Keeping the lights on while measuring electrical and mechanical activity of heart and stomach muscles.

Name: Haley Nesmith Patton, Doctoral Student

Department: Biomedical Engineering

Tell me more: Patton is studying cardiac and gastric electromechanics at high spatial resolution using custom optical mapping systems in the lab of School of Engineering Professor Jack Rogers, Ph.D. “As part of our optical mapping system, we use a voltage-sensitive dye,” Patton said. “We excite the dye with densely spaced, high-power LEDs. We designed and 3D-printed a water-cooled light assembly to hold the LED circuit boards; we also printed filter holders that are placed atop the assembly.”

Printer: Formlabs stereolithography resin printer, Lister Hill Library. “We needed to use a material that does not leak water,” Patton said. “SLA printing allowed us to print a watertight model without any further material processing.”

Patton's water-cooled light assembly to hold LED circuit boards

Patton's water-cooled light assembly to hold LED circuit boards

ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Why use 3D printing in your research? Patton offered three reasons:

1. Speed. “3D printing enables us to design custom parts with complex geometries and then rapidly print and iterate on a design.”

2. Cost. “There are, of course, other ways we could manufacture these parts; but 3D printing in this case was cheaper, easier, quicker and more repeatable than alternative methods.”

3. Reproducibility. “As researchers who develop new tools, we aim for our tools to be easily reproduced by other groups. By designing a printable 3D model, we can easily distribute the model and assembly instructions to research groups interested in replicating our system.”

Eric Plaisance, Ph.D., Department of Nutrition Sciences, and Dorothy Ogdon, UAB Libraries

Eric Plaisance, Ph.D., Department of Nutrition Sciences, and Dorothy Ogdon, UAB LibrariesSTEVE WOOD | University Relations

Project: Custom case for UAB Football GPS units

Name: Eric Plaisance, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Program Director of the Community Nutrition Certificate

Department: Nutrition Sciences

Tell me more: While Plaisance was chair of the Department of Human Studies in the School of Education (he moved to the School of Health Professions in 2022), he and the faculty developed a new concentration in sports physiology and performance as part of the Bachelor of Science degree in kinesiology. This led to conversations with Lyle Henley, director of Sports Performance for the UAB Football program. Henley mentioned that Blazer Football was outfitting players with small sensors during practice to measure speed of movement, distance traveled and a host of other parameters to maximize performance and reduce injury.

“The device was outfitted in a harness under the shoulder pads, but many of guys said it wasn’t comfortable — it was tight,” Plaisance said. He offered to work on an alternative, and thinking that 3D printing might help, he learned about the capabilities of the UAB Libraries labs from Dorothy Ogdon. “I told her about the project and asked her to meet with Lyle and me,” Plaisance said. “She came to the Football Operations building with a tape measure, went back and started printing.”

Prototypes of GPS cases for UAB Football players created by Plaisance and Ogdon

Prototypes of GPS cases for UAB Football players created by Plaisance and Ogdon

STEVE WOOD | University Relations

The final product looked like a phone case and was about the size of a deck of cards. Plaisance drilled some holes, added a bungie-cord system to secure it to the back of the shoulder pads, and it worked. “Dorothy printed 44 of these — one for each of the first- and second-teamers on offense and defense, and they wore them throughout the season last year,” Plaisance said.

While the new system was more comfortable and did a great job of protecting the expensive GPS units, it turned out to be less effective for capturing player heart rates, so the team has opted to go back to the original front-mounted system. Nevertheless, it was a successful collaboration, Plaisance says. “Where else do you see a librarian, a researcher and a member of the Athletics department working together like this?” he asked. “This was a really cool project.”

Printer: LulzBot Taz 6 filament printer, located in Lister Hill Library 3D printing, TPU filament.

Jeremy Hydler, Facilities

Jeremy Hydler, FacilitiesANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Project: Fixing failed controllers on HVAC units across campus

Name: Jeremy Hydler, Engineering Manager, Campus Maintenance

Unit: Facilities

Tell me more: “We have a lot of older HVAC units on campus, and as these components age and the manufacturers stop supporting them, parts can be hard to get,” Hydler said. In one system found throughout the campus and hospital, a common point of failure is a plastic cylinder used to reduce wear on moving components, known as a bushing, found in vent controllers.

“When you are sitting in your office or classroom and you have air that is coming out of a vent in the ceiling, up in the ceiling is a box that has a little controller,” Hydler explained. “The controller opens a big butterfly valve in the box to provide more air and closes it when the temperature is right. This bushing sits between the motor that opens the valve — the damper — and the damper shaft. When that little bushing breaks or strips out, the motor can no longer open the damper and you don’t get air. Other than that, the controller is all right. But if you think of how many rooms we have on campus, you can imagine how many of those boxes there are.”

3D-printed bushings to replace broken parts in UAB HVAC units

3D-printed bushings to replace broken parts in UAB HVAC units

ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

The Facilities team had already checked with the manufacturer to buy replacement bushings, “but they couldn’t get them,” Hydler said. Then Chris Clark, an instrument and control technician in Hospital Maintenance with a personal 3D printer at home, came up with an idea. He built a 3D model of the bushing and started printing them on his printer. The solution worked, “and that has been pretty successful,” Hydler said.

After Hydler joined UAB last year, his maintenance team let him know they were running out of the bushings that Clark had printed and wanted more. “We are using these in production now,” Hydler said. “So we needed to have a more established process.” Clark gave Hydler his 3D model file, and Hydler contacted Dorothy Ogdon and Patrick Boggs at UAB Libraries for assistance in getting set up for regular use. “We are now testing with different materials and printer settings, such as temperature,” Hydler said. “Test prints are being done, and we are installing them in units to see if there are adjustments that need to be made. Patrick has helped me more than just the run-of-the-mill user, which I certainly appreciate. We have been able to leverage his expertise to get us a usable part more quickly.”

Hydler sees a larger role for 3D printing in maintaining UAB’s vast physical plant. “One of the issues we have had with supply chains since the pandemic is that, even if something is available, you may not get it for a long time,” Hydler said. “I’m thinking if we develop skill with 3D printing in Maintenance that it would be a huge advantage for us.”

David Resuehr, Ph.D., and J. Bradley Barger, Ph.D., Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology

David Resuehr, Ph.D., and J. Bradley Barger, Ph.D., Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative BiologyANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Projects: Novel teaching tools for professional students in the health sciences

Names: David Resuehr, Ph.D., Associate Professor, and J. Bradley Barger, Ph.D., Assistant Professor

Department: Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology

Tell me more: Resuehr and Barger teach anatomy to students from the Heersink School of Medicine and the schools of Dentistry, Optometry and Health Professions and are co-directors of their department’s master’s degree in anatomical science.

They began working with 3D printing in 2017 after buying a printer with a small grant. “Our original idea was that we have bones in the lab, and we wanted to print soft-tissue structures to use with the bones,” Barger said. Although that idea did not work out, he and Resuehr found many other projects that did; they now have several filament printers, ranging in price from $300 to $5,000. “Commercially available anatomy models typically cost anywhere from a few hundred dollars to several thousand dollars,” Resuehr said. “You can buy printer filament and print a model for usually less than $10.”

A sampling of the 3D-printed teaching tools created by Resuehr and Barger

A sampling of the 3D-printed teaching tools created by Resuehr and Barger

ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Many of Resuehr’s 3D-printing projects relate to teaching future doctors to use ultrasound, which he has been advocating for in the School of Medicine for a number of years. “I want them to better understand how the view on the screen comes to be,” he said. “It is complicated as we flatten complex three-dimensional anatomy into a 2D grayscale picture. It takes some practice to learn to do it correctly.” Resuehr created a model with embedded simulated blood vessels to help students learn to catheterize them and pick up on fluid flow with ultrasound so they would learn whether “the fluid is A: flowing and B: toward you or away from you,” he said. “You could visualize it in 3D and correlate the screen with the target.”

Resuehr and Barger have created scannable, injectable knees and fingers as task trainers. Their work has resulted in several publications, including a knee paper from 2019 and Resuehr’s paper on a hip joint model, which was an editor’s pick last November in the journal EMJ. The hip (useful for practicing ultrasound-guided hip joint injections) and an arm with embedded blood vessels (for practicing ultrasound-guided blood draws from difficult-to-reach deep veins) were created using a handheld 3D scanner. They used the scanner to scan a torso model and a human arm, computer-generating and 3D-printing models/molds and using ballistic gelatin in conjunction with these to create trainers. Resuehr also 3D-printed a heart in several “slices,” like those made with a CT scanner image, held together by magnets. He uses it as a teaching tool and presented it at a Research and Innovation in Medical Education conference at UAB several years ago.

One of the anatomy team’s largest recent projects was led by Assistant Professor Danielle Edwards, Ph.D.: printing 80 skulls with articulated jaws (two every eight hours, over several weeks) for UAB dental students to use starting in the spring 2022 semester. “We gave each student their own individual skull they could take home,” Barger said. “That course is a half-semester — they get a lot of anatomy in a little time.” Although the anatomy lab is open 24 hours a day for studying, “having this skull you can keep in your bag and work with whenever you want” was a real improvement, Barger said. “The students loved it and thought it was useful, and our research” — now being prepared for publication — “did show an increase in grades.” The researchers also wanted to know if the skulls would survive student use, including “will it melt if you leave it in a car?” Barger said. “We got them all back in the end, and in good condition.”

Cost + customization: The price tag for the skull project illustrates the advantages of 3D printing. “It took several weeks and a couple of hundred dollars total” (with funding from Edwards’ grants) to complete the project, compared with commercial skulls that “are a couple of hundred dollars each,” Barger said. The skulls started as a file downloaded from the 3D printing hub Thingiverse, “plus, we customized them with holes and spaces that you don’t always see that are important for dental students.” The mandible was attached in the original file, but Barger and his co-workers printed it separately and connected it with the rest of the skull using springs, so it was articulated. “The original teeth were all in one piece too, but we remodeled them to give them surfaces,” Barger said.

3D resin printers at the Lister Hill Library 3D Printing lab on the first floor.

3D resin printers at the Lister Hill Library 3D Printing lab on the first floor.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Projects: 3D renal proximal tubule chips for disease modeling and drug toxicity testing

Name: Leslie Donoghue Seeley, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Student

Department: Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiovascular Disease

Tell me more: Seeley, who defended her dissertation for a doctorate in biomedical engineering in spring 2023, did her research in the Cardiovascular Bioengineering Lab led by Professor Palaniappan Sethu, Ph.D. (Sethu is also associate professor on the Department of Biomedical Engineering, a joint department of the Heersink School of Medicine and School of Engineering.) Seeley’s project focused on the proximal tubule, a portion of the kidney that is particularly susceptible to drug injury.

“We are trying to emulate the in vivo physiology and apply drugs to the system,” Seeley said. In recreating the dynamic environment of a real kidney, “we subject biomechanical forces of fluidic shear stress, pressure and stretch to in vitro cells using specialized pumps and tubing.” Seeley designed and created 3D-printed devices so she could tissue-engineer and image the proximal tubule and its associated vasculature. Her models contain three or four cell types in a hydrogel, with input and output valves connecting to a pump that recirculates media through the system.

“Once you perform the cell culture and seeding protocols, you can identify issues in the device’s design and where it could be improved,” Seeley said. “One of the great advantages of the 3D printers on campus is that I can easily execute a new print or iteration of an existing design. Having the 3D-printing lab just down the street makes it easy to tweak and optimize your design.” Seeley would sometimes print up to nine variations at a time, and she says she has reached into the hundreds over the course of her dissertation work. “Patrick [Boggs, technology manager for the 3D-printing labs at UAB Libraries] and I have become buddies; I have been there a lot,” Seeley said.

Printer: Formlabs stereolithography resin printer, Lister Hill Library 3D Printing. “There are several resin types that are even biomedically friendly,” Seeley said. “I specifically used the resin of the SLA printer so we can sterilize it using our normal protocol methods in a gravity autoclave cycle.”

Ian Berg, Ph.D., Division of Cardiovascular Disease

Ian Berg, Ph.D., Division of Cardiovascular DiseaseANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Project: Stretching and pressuring different types of heart cells as they mature.

Name: Ian Berg, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Scholar and NIH T32 Fellow

Department: Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiovascular Disease

Tell me more: Berg, like Seeley (above), is part of the Cardiovascular Bioengineering Lab of Professor Palaniappan Sethu, Ph.D. “My main project involves differentiating induced pluripotent stem cells into different heart cell types, then taking those clumps of cells, assembling them into more complex structures and exposing them to some of the mechanical stimuli of an actual heart’s environment,” Berg said. “Applying those real levels of pressure and stretch is where the 3D printing comes in. We engineer devices that allow us to do that. I will print out a master mold of the device that we want to make, then take a silicone-based polymer and pour it over this master mold. This silicone is very compatible with cell culturing.”

Berg's resin-printed molds for his research in heart cell differentiation

Berg's resin-printed molds for his research in heart cell differentiation

ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Printer: Formlabs stereolithography (SLA) resin printer, Lister Hill Library. “You can get really fine-detailed resolution with resin printing — nice, smoother surfaces — which is important when making these devices for 20- to 50-micron-sized cells,” Berg said. “The resin printers give us higher spatial resolution and more control over the surface properties of the material.”

Maker space: In addition to his research, Berg loves tinkering in general. He is a member of Red Mountain Makers, a nonprofit “community fabrication center” located in the Hardware Park building at Ninth Street and Fourth Avenue North. Among other projects, he has worked on wood and plastic engravings and made decorations, he said: “There are also a whole bunch of classes that members and non-members can take; 3D printing is one thing we do here, but we also have a laser cutter, saws and drills and a workshop. I have definitely used these tools to enable my research as well.”

Each of the printers in the Sterne Library 3D Printing lab is named for an important figure in UAB history.

Each of the printers in the Sterne Library 3D Printing lab is named for an important figure in UAB history.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Project: Custom applicators for radiation therapy

Name: Dennis Stanley, Ph.D., Assistant Professor and Chief of Adaptive Therapy

Department: Radiation Oncology

Tell me more: The department has had its own 3D printer since 2020, which is used mainly for “design fabrication,” Stanley said. “A lot of what we do is basically proofs of concept before we get something made from acrylic or steel or another material. Those are really expensive; making it out of plastic is easier, so you can make sure it all works.”

But Stanley sees a big future for 3D printing for patient care. “We’re starting to find really good uses, especially now with some of the more advanced material deposition printers,” Stanley said. “Those are going to really change the way we position and monitor patients over time.”

An example, already in use in the department, is the creation of custom applicators for radiation treatment in particular areas of the body with irregular geometry, such as the nose and foot. “If we are treating a patient’s face, for example, we can scan the face and create a mold of the nose” with a 3D printer, “then create a molded wax that can drive a radioactive source to treat portions of the nose.”

Printer: The department’s own filament printer is sufficient for most projects. But for a recent use case, Stanley contacted Patrick Boggs, technology manager for the 3D printing labs at UAB Libraries (and a former member of the Rad/Onc department). “We wanted to evaluate how well the optical-based imaging systems used in the stereotactic radiosurgery program handled different skin tones,” Stanley said. “We got this very specific material that they use in the fabrication of prosthetics” that would work on the UAB Libraries Formlabs resin printer “and used Human Atlas [software] to print an axial slice of the same head multiple times using various skin tones. That allowed us to compare the operational characteristics to see if they have a predisposition for certain skin tones and verify that they are working correctly.”

A bioprinter in the Lister Hill Library 3D Printing lab.

A bioprinter in the Lister Hill Library 3D Printing lab.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Project: Creative looks for up-cycled soap

Name: Judith McBride, Senior Safety Officer – Labs and Chemical, and Rani Jacob, Ph.D., Chemical Hygiene Officer – Facilities

Department: Environmental Health and Safety

Tell me more: What do cooking fat and 3D printing have to do with lab safety? Several years ago, McBride and Jacob received a QEP grant to develop a team-based lab safety training program for undergraduate students at UAB. That project evolved into a course in the UAB Honors College on lab safety, sustainable science and environmental regulations, including fire extinguisher training, hazard communication, OSHA regulations and more.

These are not naturally the most fascinating topics, Jacob notes. But it is essential information for the large proportion of Honors College students who are interested in STEM fields. “Our idea was to have a hands-on component in which students transformed waste materials and byproducts into useful commodities — and then sneak in the safety and regulatory component,” McBride said.

At a conference, the UAB duo heard faculty from another university talk about making soap from biodiesel byproducts. “We thought, ‘We can get cooking oil from the local restaurants, add discarded sodium hydroxide from the laboratories, and we can make our own soap,’” McBride said. Since then, she and Jacob have developed two seminars — a 100-level course in the fall semester and a 300-level class in the spring — that have become perennial favorites. “We are always full,” McBride said.

The students learn the chemistry of soapmaking — saponification — and how to develop standard operating procedures and work safely in the lab during the process, Jacob said: “All you need is cooking oil, sodium hydroxide [lye] and water.” (To lighten the soap color, Jacob and McBride use olive oil and coconut oil along with the vegetable/canola oil from UAB Dining.) “You don’t even need heat,” McBride added, “but without it, you will need to let the soap sit for six weeks. With heat, it is literally ready in about six to eight hours.”

Where does 3D printing come in? “Each group has to create a marketing strategy and logo as part of the assignment,” McBride said. “They pick a name for their product and then design a stamp, which is 3D-printed at UAB Libraries” and pressed into each bar. Dorothy Ogdon talks to the class about 3D printing and explains the process. “I’ve noticed lately that about half of the upperclassmen have already had experience with 3D printing, which is interesting,” McBride said.

“The students get really thoughtful,” McBride said. “They can choose their colors and their fragrances. Some go for a really pure product with no fragrances and maybe a little oatmeal. We also have seasonal molds — tulips and roses in the spring and Christmas trees and bells in winter.”

“They have interesting names and wrapping choices, too,” Jacob said. “Peachy clean, Bee clean.”

Over the course of a year, the classes generate 40 pounds of soap, “which is donated to Blazer Kitchen,” Jacob said. “They have been really happy with it because they had not been able to get a regular supply of personal care products.”

“The thing that makes me happiest is that we have had several students who have gone on to volunteer at the Blazer Kitchen” because of the course, McBride said.

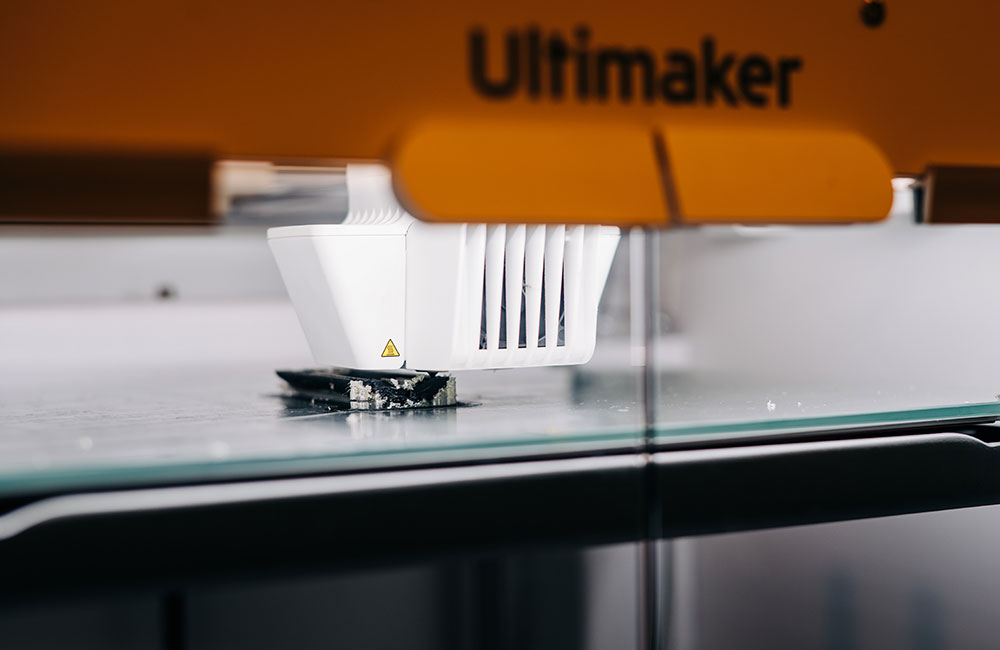

An Ultimaker 3D filament printer in action at Sterne Library 3D Printing.

An Ultimaker 3D filament printer in action at Sterne Library 3D Printing.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Project: Printing guides for dental implant surgery

Name: Ryan Seeley, DMD, M.D., Resident in Oral Surgery

Department: Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dentistry

Tell me more: Seeley was introduced to 3D printing at Lister Hill Library several years ago during dental school, when he worked on a test 3D print of a mandible (the lower jaw). “Fast forward a few years, and we recently got a 3D printer for our oral surgery clinic at the dental school and have been making custom guides for dental implant surgery,” he said. Each of these guides is patient-specific and created using “cone-beam CT radiology imaging and a high-definition optic intra-oral scan of the patient’s teeth,” Seeley said. “We then use a program that unifies this information and allows us to design a custom plan for the patient.”

That process takes about an hour, then another hour for the 3D print and about 30 minutes for post-printing processing. In practice, however, because this is a training clinic, the proposed surgical plans require faculty reviews, so the average time from initial patient evaluation to dental implant surgery is about two weeks, Seeley says.

But the guides do not each require an hour for printing. “We can print about six to 10 different custom guides all at the same time,” Seeley said.

Printer: Formlabs 3B resin printer in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. “We require a high precision in order for the guide to sit correctly on the occlusal surface of the patient’s teeth,” Seeley said. (The occlusal surface is the biting surface of the teeth.)

Getting started with 3D printing at UAB Libraries

UAB Libraries has 3D printers at Lister Hill Library and Sterne Library.

Sterne Library 3D Printing, located on the ground floor in Room 146, has five filament-based printers — these are the typical 3D printers you have probably seen, in which the print head melts a thin layer of plastic filament to build an object from the ground up. “If you touch them, you can feel a layer line on the surface where each individual layer of plastic sits,” said Dorothy Ogdon, associate professor and head of Emerging Technology and System Development for UAB Libraries.

Lister Hill Library has both filament printers and two resin printers from Formlabs in Lister Hill Library 3D Printing, located on the first floor of the building in Room 115. “Resin is still additive manufacturing, one layer of time; but the layers are much smaller — 0.5 microns instead of 0.5 millimeters,” Ogdon said. Resin printing is also called stereolithographic printing. Instead of building from the base upward, as in filament printing, a resin printer works from the top down, with a moveable platform dipping into a pool of photo-sensitive resin, which is hardened by an ultraviolet laser beam. Different types of resin are available, including one that is biocompatible and can be cleaned in a typical lab autoclave.

The tradeoff for the improved scale and biocompatibility of resin printing is “uncured resin on the surface once printing finishes,” Ogdon explained. “You have to wear gloves and eye protection to rinse that resin off with isopropyl alcohol, and you can use heat and light to cure the materials further to make them harder.”

Required training course

UAB Libraries requires that all users complete a 3D Printer Training course before users can start printing their own projects. (Find upcoming class times and register here.) During the training, they are given access to printer queues for both Sterne Library and Lister Hill Library 3D printing via 3DPrinterOS. 3DPrinterOS is a cloud-based system that lets users monitor the ongoing print queue to see when printers are available and check the progress of their jobs; several of the 3D printers managed in 3DPrinterOS have cameras attached so users can watch how their prints are coming along. Users also automatically receive a time-lapse video of their items being printed via email once the objects are complete.

“If you want to 3D-print an item, you start by logging in and doing your layout,” Ogdon said. “We teach people how to get started with that. And then our students come in to work every day and print the next items in the queue. You can do all your printing setup remotely on any device with a web browser, including a smartphone.”