When you fall asleep tonight, an army of workers will keep the world going, but they’ll pay a price.

In the United States, some 15 million workers are on evening or night shifts, or rotate on and off these shifts: nurses, factory workers, gas station attendants. Decades’ worth of studies have shown that working at night increases a person’s risk of heart disease, heart attacks, diabetes, obesity, cancer and other conditions. A major reason is because night shifters tend to sleep poorly — and as scientists continue to discover, proper rest is essential to good health.

In the United States, some 15 million workers are on evening or night shifts, or rotate on and off these shifts: nurses, factory workers, gas station attendants. Decades’ worth of studies have shown that working at night increases a person’s risk of heart disease, heart attacks, diabetes, obesity, cancer and other conditions. A major reason is because night shifters tend to sleep poorly — and as scientists continue to discover, proper rest is essential to good health.“We’re a diurnal species,” said UAB chronobiologist Karen Gamble, Ph.D., who specializes in the habits — and hormones — of night shift workers. “We want to sleep at night.” Gamble has identified practical “sleep strategies” that can help workers lower their health risks. She has also unraveled parts of the maddeningly complex genetic networks powering our internal molecular clocks, which play a key role in sleep troubles. Now Gamble, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology in the UAB School of Medicine, believes science has the data, and tools, to reshape shift work entirely.

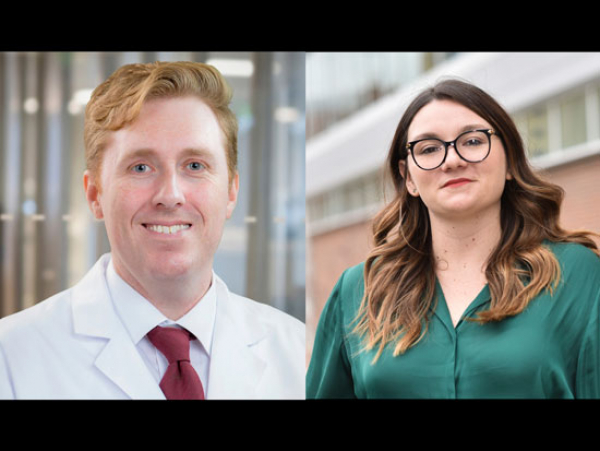

Working with Patricia Patrician, Ph.D., RN, FAAN, Donna Brown Banton Endowed Professor in the UAB School of Nursing, Gamble is exploring an intriguing solution: staff the night shift with the workers who are genetically best suited to the job.

Presenting seminar on November 17

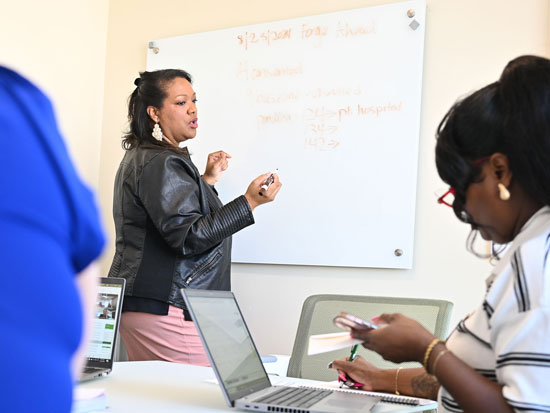

Patrician and Gamble are giving the seminar, “Cognition and Vigilance in Shift-Working Nurses” as part of Patrician's appointment as the Donna Brown Banton Endowed Professor, on Tuesday, November 17, at 10 a.m. in the UAB School of Nursing Room 1020, 1701 University Blvd. A reception will follow. Everyone is invited to attend but must click here to RSVP.

The Donna Brown Banton Endowed Professorship supports the named faculty member in their pursuit of research/service learning in the area of improved patient care. The Donna Brown Banton Professor then reports back to the community each year in the form of a seminar disseminating information and knowledge learned from their scholarly work for the purpose of helping nurses and other caregivers improve patient care.

Impacting Nurses

In most U.S. hospitals, nurses on the night shift work 7 p.m. to 7 a.m., three days a week, followed by four days off. And what do the nurses do on their off days? “Ninety-seven to 98 percent of them go back to sleeping at night,” said Gamble. “If you have any kind of family responsibilities, or social life, you have to be up and active at the same time as everybody else on your days off.”

But jumping back and forth between sleep cycles isn’t easy. “Nurses suffer from social jet lag,” Gamble explained. That is, the time clocks in their brains — and the subsidiary clocks in their guts, livers and other organs — are out of sync with each other and the environment. In a recent paper, Gamble pointed out that this sleep flip-flop is equivalent to flying a Tokyo-San Francisco roundtrip every few days.

Sleep troubles also increase a nurse’s risk of making mistakes. “When you aren’t getting enough sleep, and your circadian rhythms are misaligned — at the end of three consecutive night shifts, for example — it can be hard to make the right decisions,” Patrician said.

Early birds and night owls

Some nurses like the night shift, but mostly the duty falls to younger, less-experienced staff. Gamble and Patrician have another idea: What if you changed the shift system, so nurses who are better suited to night work pull these shifts more often?

The key concept here is “chronotype.” Some people are real early birds, others are extreme night owls, and most of us are somewhere in between. “It follows a nice normal distribution,” Gamble said. You can measure chronotype through a simple survey, such as the widely used Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (take it yourself at that link). If you wanted to be more precise, you could examine levels of melatonin in the saliva. Melatonin is a hormone that drives sleepiness; it starts to rise in the early evening and peaks in the middle of the night. Another measure is core body temperature, which also follows a regular, even rhythm when we’re functioning properly, although it can be influenced by sleep and exercise.

This spring, a team of German researchers published a groundbreaking study in the journal Current Biology; the same issue included a commentary on the study from Gamble and Martin Young, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Division of Cardiovascular Disease at the UAB School of Medicine. Using the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire, the German team reshaped the work schedule at a steel factory. “It was really exciting when I saw this paper come out, because this is the first time that somebody actually tried to take what we know about circadian biology and design a shift system based on that,” Gamble said. “They eliminated all night shifts for the very early morning people, and all early morning shifts for the very late chronotypes.” Each group made up the difference by adding in more shifts during their preferred times. The “middle-of-the-road” chronotypes kept their existing schedules, split between morning, afternoon and night shifts.

“The early chronotypes really benefitted from this,” Gamble said. “Their sleep duration and sleep quality improved, and they reported feeling better overall and that they had more time for leisure activities.” The researchers also saw an improvement in social jet lag, the “mismatch between your internal clock and your external environmental demands,” said Gamble.

“The early chronotypes really benefitted from this,” Gamble said. “Their sleep duration and sleep quality improved, and they reported feeling better overall and that they had more time for leisure activities.” The researchers also saw an improvement in social jet lag, the “mismatch between your internal clock and your external environmental demands,” said Gamble.Most of us experience this naturally. “Lots of people stay up late and get sleep deprived during the work week, and then on the weekends they try to sleep in,” Gamble said. “By doing this shift schedule intervention, the German group reduced the social jet lag by one hour among the morning types.”

The night owls also improved, Gamble notes, although they didn’t see as many benefits from dropping their morning shifts as the early birds did from skipping their late shifts.

Turning data into better decisions

Patrician, a former active duty member of the Army Nurse Corps, spent a decade with her research team building the Military Nursing Outcomes Database, which tracked patient falls, medication errors, needle sticks and other “nursing quality indicators” at 13 military hospitals. “We wanted to know how nurses are impacting quality, and which actionable managerial decisions — the staffing levels on various shifts, a unit’s practice environment, the experience level of nurses — affect those measurements,” Patrician said. Insights gleaned from the database — the importance of registered nurses in reducing errors, for instance — are now being used to improve care at all Army hospitals, Patrician noted.

Patrician has similar hopes for her work with Gamble. With funding from the School of Nursing dean’s office, Patrician and Gamble launched a small pilot study last year. They recruited 30 nurses: 15 working day shifts, 15 working night shifts. Participants received a battery of tests on their last days on shift, followed by more tests on their last days off, to see how well they had recovered. These included a psychomotor vigilance exam, which measures attention and reaction time; a mathematical addition test to gauge cognitive performance; and a timed drug calculation test as a work-related test of cognition based upon a function that nurses must perform daily.

The researchers are now analyzing their data to determine if the nurses — whether on day shift or night shift — performed better when they were in circadian alignment. The researchers are also collecting food diaries, “to see what kinds of nutrients the nurses are taking in, and at what times,” Patrician said.

Fixing abnormal rhythms

For long-term night shifters, there are research-based methods to improve sleep, including supplemental melatonin and controlled exposure to light, Gamble explains. “If you give melatonin in the late afternoon, it will advance your clock, and exposure to light in the early morning hours will help you get up earlier,” Gamble said. “If you could use them both together you might be able to shift an extra one and half hours per day.”

That won’t help nurses, however. “If you’re talking about three days on the night shift and then four days off, you’re never going to be able to shift a full 10 hours in three days,” Gamble said. “It’s just not biologically possible. I think the solution is a different shift system. It seems like we can take what we know about chronobiology and come up with a better way to do this.”

Gamble and Patrician are now meeting with nursing unit managers at UAB Hospital to plan a series of trials of chronotype-adapted shift scheduling.

“The idea would be basically you take your night shift workers and divide them into two groups — ones that get off at 3 a.m. and ones that start at 3 a.m.,” Gamble said. “Your early chronotypes would be the ones starting at 3 a.m., and your late chronotypes would be the ones getting off at 3 a.m., so that way no one has as far to go.”