Imagine you are an attorney preparing for a high-pressure case and feeling certain you’re up to the task but suddenly realizing that somehow you are out of sorts.

You forgot to schedule an important deposition. Your secretary has reminded you three times the location of your next meeting. This morning you needed help finding your car keys.

You have no idea what is wrong. You’re in your mid 50s and in good shape. You’re HIV-positive but taking your medication as prescribed, following to the letter the regimen laid out by your doctor. Yet something just isn’t right.

Such is the life of many in the growing population of older adults with HIV who are experiencing the onset of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder (HAND).

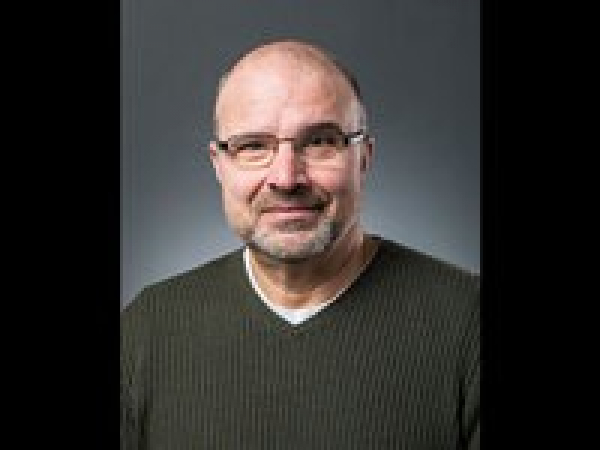

University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) School of Nursing Professor David Vance, PhD, MGS, MS, has received a two-year, $404,250 R21 grant from the National Institutes of Nursing Research (NINR) for his project “Individualized-Targeted Training in Older Adults with HAND” to develop cognitive training interventions to improve everyday functioning and quality of life of those with HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder.

As medicines to control HIV have improved over the years, so too has the life expectancy of those living with it. But with that increased longevity has come other health issues, including dementia and other cognition-related problems that are occurring at much earlier ages in those living with HIV.

More and more, as they are aging HIV patients are asking their physicians “What’s wrong with me?” and more and more physicians are suspecting HAND and even testing for the condition. Yet after the diagnosis is confirmed there are few answers for those clouded by this fog of uncertainty.

“When I talk to physicians and other clinicians they want to know what they can do about their patients who are experiencing cognitive problems,” Vance said. “Unfortunately, right now there are few options for these patients.”

LIFE-CHANGING CONSEQUENCES

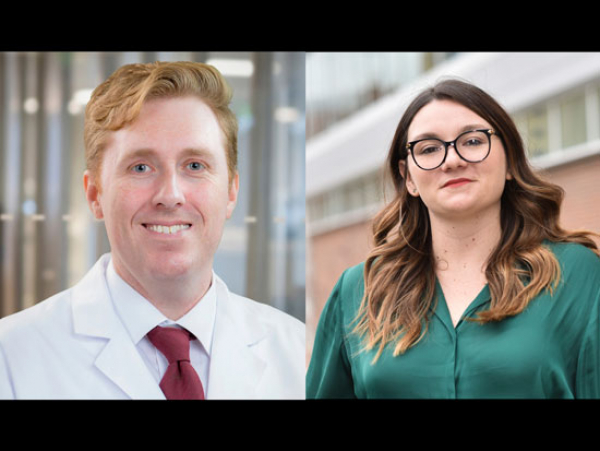

Jim Raper, PhD, CRNP, JD, FAANP, FAAN, director of UAB’s 1917 HIV Outpatient, Dental and Research Clinic and a long-time colleague of Vance’s, has heard the questions, seen the confusion and been frustrated by his inability to provide much concrete information to his patients.

He has a patient who is an attorney, and though his HIV is well controlled, increasing problems staying mentally sharp and focused in the fast-paced legal world have led him to consider drastic measures.

“When’s he’s preparing for court he just doesn’t feel as confident as he used to,” Raper said. “He has actually considered closing his law practice down for fear that he is not providing his clients with the level of expertise he has provided them before.

“That is why I am so excited about working with David on this project. It is critical to have someone like him who has been in this field for so long and understands its nuances developing potential innovative interventions.”

Vance’s concept is simple. He plans to test whether or not previous speed of processing interventions developed to help older adults with dementia and other cognitive issues who are not HIV positive will also work with older patients living with HIV.

“Past studies have put older adults with cognition problems in driving simulators to see if their driving safety could be improved through training,” Vance said. “We know from those previous studies that some people who go through this training do experience an improvement.

“So if something like that works for older adults without HIV, why can’t it work in older adults with HIV?”

SUPPORTING SPEED OF PROCESSING

Vance defines speed of processing as the rate in which a person processes information from start to finish.

When we are younger our speed of processing is lightning quick, like the function of a computer. As part of the normal aging process, our neurocognitive signals begin to degrade, our cognitive efficiency lessens, and we take longer to memorize information or perform tasks.

For someone with HIV, this process often kicks in at an even earlier age due, in part, to low-grade inflammation trigged by their HIV.

“The brain is being inflamed and is not as productive as it used to be which contributes to memory lapses, forgetfulness and the general fogginess many older patients living with HIV experience,” Vance said. “In fact, 50 percent of people living with HIV experience HAND, which is why we are focusing on it with this study.

“We know that if they have this disorder, it is more than likely impacting their medication adherence, financial management, mood and much more.”

For the study, Vance will target 146 people – 73 who will receive the interventions and 73 who will make up a no-contact control group. A battery of neuropsychological tests will be administered to all patients to determine if they are experiencing HAND and what their individual cognitive deficits are. Vance and his team will then provide individualized training to those in the contact group in hopes of helping them improve in their individual deficit areas.

“If someone has an issue with attention for example, we will focus on improving their cognitive ability in that area,” Vance said. “We will work with them with the hope that the next time we assess them they will have shown significant improvement or perhaps will no longer have the problem at all. That is the crux of this grant.”

MUCH MORE TO COME

Early this decade, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that by 2015 nearly half of those living with HIV in the United States would be over the age of 50. The United States Senate Special Committee on Aging now estimates that by 2020 the figure will be nearly 70 percent. As the overall numbers rise, so does the urgency to find ways to help with HAND.

It is one of many reasons Sonya Heath, MD, a colleague of Raper’s at the 1917 Clinic, is excited to see Vance receive this crucial NINR funding.

“Dr. Vance’s study is very timely in that it is going to begin to help us really understand the scope of this disease,” Heath said.

Dr. David Vance's research into the cognition problems of older adults with HIV is cutting edge in the field and gives hope that the quality of life of this growing population can be greatly improved in the coming months and years.David Vance with brain modleHeath believes Vance’s work will benefit the older HIV population in two important ways. In addition to formulating interventions and training techniques to improve quality of life for those diagnosed with HAND, it will also lead to increased screening of potential HAND patients at earlier stages.

Dr. David Vance's research into the cognition problems of older adults with HIV is cutting edge in the field and gives hope that the quality of life of this growing population can be greatly improved in the coming months and years.David Vance with brain modleHeath believes Vance’s work will benefit the older HIV population in two important ways. In addition to formulating interventions and training techniques to improve quality of life for those diagnosed with HAND, it will also lead to increased screening of potential HAND patients at earlier stages.“I think that with research like this, we are actually going to find that many more patients have neurocognitive issues,” Heath said. “To a certain extent when you don’t have an intervention or a treatment you may recognize those that have very progressed neurocognitive dysfunction but not some of those with milder impairments. When we have something to offer them, it will only increase our screening and recognition of patients with neurocognitive disorders.

“Finding these patients earlier in the process will be beneficial to preventing progression of this disease down the road.”

DIFFICULT TO WATCH

Raper tells his patients that if he does his job well, they will be able to continue working, being productive and doing all the things they want to do in their lives. That is why it is heart-wrenching for him as a clinician when patients living with otherwise well-controlled HIV come to him ridden with anxiety as they sense things changing.

“They say, ‘I’m having trouble keeping it together,’ or ‘I’m having difficulty concentrating,’” Raper said. “They’ll say ‘You say my numbers look good’ or ‘I’m not that old.’ Then they’ll almost always ask, ‘What’s happening to me?’”

The question always hits him hard because there is so little he can do.

“Part of the reason we come to work every day is to alleviate suffering,” Raper said. “Most clinicians get their heart strings pulled from time to time when you see patients who aren’t doing as well as you would like through no fault of their own. Progression of a disease is always difficult to watch.”

Raper is encouraged by Vance’s idea to incorporate interventions that have proved successful in other areas.

“Conceptually it makes sense,” Raper said. “Now we just have to test the hypotheses.”

THE SEARCH CONTINUES

The situation hits home with Vance personally through friends who are living with HIV and suffering from cognitive problems. A colleague in Mississippi has HIV-associated dementia yet still drives because he has to maintain his everyday functioning. Other acquaintances face equally daunting challenges.

All are compelling reasons why Vance, who is also in the midst of work on a five-year, $2.86-million R01 grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health that also focuses on enhancing cognitive functioning of older HIV patients through of speed of process training, continues to search so diligently for clues to unravel the mystery.

The R01 study is examining the dosage level of speed of processing training to improve a patient’s cognitive ability which may also reduce depression and improve driving safety, medication adherence, loss of control, self-rated health and health-related quality of life. The R21 study is focused on changing the diagnosis of HAND by individualized targeted cognitive training in the cognitive domain patients are experiencing a deficit -- in essence trying to reverse or cure the cognitive symptoms of HAND.

“If we can prevent, or even slow down, cognitive problems in our patients, we help them remain healthy and independent with a higher quality of life,” Vance said. “We must always remember that there is no health without mental health, and that is certainly true in this case.”