For individuals living with chronic low back pain, the condition leads to more than just discomfort. Categorized as back pain lasting more than 12 weeks, and one of the most common forms of pain experienced in the United States, chronic low back pain can lead to costs from lost wages, reduced productivity, and more, amounting to about $100 billion annually. It is also associated with depression, stigma, anxiety and disproportionately impacts U.S. residents who identify as African American or Black more than other racial/ethnic groups.

For individuals living with chronic low back pain, the condition leads to more than just discomfort. Categorized as back pain lasting more than 12 weeks, and one of the most common forms of pain experienced in the United States, chronic low back pain can lead to costs from lost wages, reduced productivity, and more, amounting to about $100 billion annually. It is also associated with depression, stigma, anxiety and disproportionately impacts U.S. residents who identify as African American or Black more than other racial/ethnic groups.

While these statistics are known, there is a gap in knowledge regarding the cause of these racial differences in chronic lower back pain, as well as how these factors lead to worse outcomes.

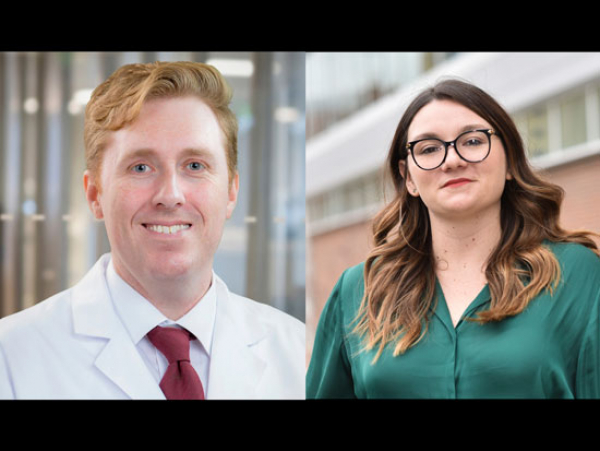

University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Nursing Assistant Professor Edwin Aroke, Ph.D., CRNA, will fill this gap in knowledge through a four-year, $1.7 million R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health.

“We all experience back pain,” Aroke said, referencing the times that many people wake up with a sore back or experience pain after sitting at a desk all day. “For many people, going on a walk or doing some stretching alleviates the pain. But the critical question becomes, ‘Why, for some people, does this pain persist?’ The question progresses from ‘why does this hurt’ to ‘how did this become chronic’?” Unfortunately, the exact cause of chronic low back pain is not known for most individuals, and they are said to have non-specific chronic low back pain.

“Looking at chronic low back pain, Black and Brown individuals tend to have worse and more severe pain and have worse outcomes,” Aroke said. “We know that biopsychosocial factors play a role. For instance, when you ask individuals how they see themselves on a social ladder, we realize that white people report less depressive symptoms and less back pain as social standing increases. For Black and Brown individuals, however, they have more depressive symptoms and more back pain.”

Aroke will study the role of epigenomics in the presence and persistence of non-specific chronic back pain, especially for Black and Brown individuals.

Epigenetics is the study of genes that can become activated or silenced within the body in response to environmental factors.

“We believe that Black and Brown people have more stressful life experiences. Each time the body goes through stress, it gives a signal to produce stress hormones—like cortisol—to allow the body to manage, and epigenetic is one way by which the body activates the genes to produce stress hormones,” Aroke said. “When you experience a lot of stress, however, the body can fail to adapt after an insult or face what we call ‘wear and tear’.”

This change can happen, Aroke said, after the body realizes that a mechanism is constantly turned on; it may choose to remain on, rather than go through the process of turning on and off.

“Research has shown that some epigenetic changes are inheritable and can be passed on generation to generation,” Aroke added.

During the study, Aroke will analyze blood samples to study the role of epigenetics changes and uncover how this mechanism may cause and sustain racial differences in chronic lower back pain.

Ultimately, this improved understanding of the link between environmental factors such as socioeconomic status, psychological factors, discrimination, etc., and gene expression can inform future intervention studies that work to reverse the epigenomic changes caused by these environmental factors. These interventions can then go forward to improve the quality of life for patients with chronic lower back pain.

“If you want to solve a problem, you have to understand the problem. We cannot truly have equity in pain management or effectively treat pain in all populations until we understand the mechanisms behind it,” Aroke said. “This research will lay the foundation for hopefully taking that next step of seeing how we can reverse these epigenetic changes and improve quality of life and health.”

This grant marks Aroke’s first R01 grant. His mentors/collaborators at UAB are Associate Professor of Psychology Burel Goodin,PhD, and Professor of Biology Trygve Tollefsbol,PhD, both of the College of Arts & Sciences.